Dominican Republic conquers WBC and MLB itself appears next for worldwide baseball factory

SAN FRANCISCO – The revolution is here. It’s been here for a while, actually, though sometimes it takes an event like the World Baseball Classic for people who don’t recognize it to understand just how deep it runs already and how much deeper it soon will get.

For all of the romantics who babble on about how baseball mirrors life in the United States, a trite observation if ever there were one, you’re in luck, because it’s finally true. A country growing more Latin now has a sport doing the same. The Dominican Republic capping off its eight-game annihilation of the WBC with a 3-0 victory against Puerto Rico on Tuesday night wasn’t simply the story of one country asserting itself over the rest of the field. It was confirmation of how the last 50 years have turned the national pastime upside down, and how it’s not going back.

The D.R.’s Miguel Tejada doesn’t hold back for this flyball in the seventh inning on Tuesday. (AP)

The D.R.’s Miguel Tejada doesn’t hold back for this flyball in the seventh inning on Tuesday. (AP)Major League Baseball conceived the WBC almost a decade ago as a vehicle to grow the sport internationally, which never quite registered because it already is an international game. Left unsaid is that its international presence comes mostly from a commonwealth and countries that are impoverished (Dominican Republic), under totalitarian regimes (Venezuela, Cuba), with waning interest in the sport (Puerto Rico) and with its own professional league (Japan). In other words: the wrong kind of international.

Anyone who saw the D.R. rip off eight straight wins, however, can vouch that what the country brings to the game – the love that seeps from its pores, the passion that oozes from its style and the talent that imprints itself on every play – is far more important than what MLB seeks through this tournament.

It wants to monetize the game. The Dominicans just want to play it.

“Since we’re young, we want to be baseball players,” Dominican manager Tony Pena said. “That’s why you see that every day there are new players coming in. Because we all want to be players.”

[Related: Fernando Rodney’s plantain lives on during celebration]

Of the 1,284 players in the major leagues last season, 128 came from the D.R. – a full 10 percent of the league from an island of 10 million. Since 1956, when Ozzie Virgil became the first Dominican player in the major leagues, 551 more have debuted in the big leagues. Kids drop out of school as young as 10 to attend baseball academies full-time in hopes of signing at 16 years old. The evolution of Dominican baseball has turned into the revolution we see today, Robinson Cano and Jose Reyes the symbols of it as the tournament apexed.

“It goes from my dad and my uncles to Marichal to Mario Soto and Pedro Guerrero, Sammy Sosa, [Raul] Mondesi to Reyes and Cano now,” said Moises Alou, the GM of the Dominican team and a second-generation member of what’s considered the first family of Dominican baseball. “A lot of tradition. A lot of great players coming out of the Dominican. A lot of people know about the Dominican Republic because of the baseball.”

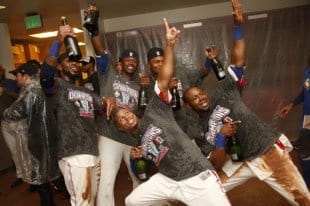

The Dominican Republic soaks in its first WBC championship. (USA Today Sports)

The Dominican Republic soaks in its first WBC championship. (USA Today Sports)This WBC, far more than the two before it, shined a spotlight on the D.R.’s brand of baseball. In the ninth inning, as Fernando Rodney prepared to close out Puerto Rico for the third time in the tournament, horns went toot-toot-toot and cowbells clanked and flags waved and pom-poms shook and everyone stood and back at home, damn near every one of the 10 million, from the rich neighborhoods to the slums and shantytowns, bellowed together as one people.

Baseball was their sport, they wanted to say, planting a flag on the United States just as Neil Armstrong did on the moon. Before the Dominicans’ semifinal game, Rodney had a plantain shipped from his hometown of Samana to San Francisco. It became his magic plantain, holstered in his waistband like a gun, representative of his country and his team.

[Y! Sports Fan Shop: Dominican Republic WBC champs apparel]

“It goes back to the plantain,” Rodney said. “That’s how we developed. With the plantain. You know what? It’s where we eat the most plantains, and we produce the greatest number of ballplayers. That’s how I see it. And this is the greatest gift we could give to our country, this trophy.”

Rodney wore a gold medal around his neck, as did all his teammates. What they had done, burying every team they faced, was remarkable seeing as only 10 streaks of eight wins or more happened all of last season in baseball. The D.R.’s five-headed relief monster – Rodney, Pedro Strop, Santiago Casilla, Octavio Dotel and Kelvin Herrera – didn’t allow a single run in 28 innings.

Considering the fashion in which they’d bowed out in 2009 – hungover, literally and figuratively, after excess partying contributed to their ouster from the Netherlands – the D.R. needed a showing to win back a country that treats the WBC with reverence. It’s not just the Dominicans, either. This is huge in Japan, Venezuela, Puerto Rico – every baseball-mad place, really, except the United States.

[Related: Brandon Phillips calls WBC participation his career highlight]

More than 35,000 people were at AT&T Park to witness the finale, a more-than-respectable number considering Team USA bombed out in the second round. A number good enough that MLB executive Tim Brosnan said commissioner Bud Selig “is 1,000 percent committed” to running another WBC, even if Selig has sworn he’ll be retired by then and 1,000 percent is sort of mathematically impossible.

MLB is so invested in this international movement, in fact, it is negotiating with the players’ association to implement a worldwide draft by 2014. And that does not sit well with its WBC champions. Pena bristled at the idea of it, telling Yahoo! Sports: “It is not going to happen. They’re trying, but we won’t let ’em. We will stop it.”

Others in the Dominican Republic have been just as vociferous about how the draft would ruin baseball in the D.R. like many in Puerto Rico claim it did when the U.S. jammed the commonwealth into its draft. Ever since, Latin American countries have been scared that the advent of a worldwide draft would similarly torpedo their baseball development, even though the relationship between Puerto Rico’s baseball decline and the draft may be more correlated than causal.

The streets of Santo Domingo enjoyed the outcome as well. (Reuters)

The streets of Santo Domingo enjoyed the outcome as well. (Reuters)Only when signing bonuses skyrocketed did the idea of a worldwide draft take root at MLB. For years, Dominican players got signing bonuses that paled compared to their American counterparts. Reyes got $15,000, Cano $150,000. Stomping on amateur money without bursting the pipeline is MLB’s next endeavor, something it must approach with great care and caution, because it understands Latin America is no longer some supplementary piece of the game. It is embedded and growing.

“We love this game,” Dotel said. “We’ve got this game in our heart. And that’s why we can’t hold it in. We’ve got to let it go out. That’s why you see a lot of exciting moments and exciting times on our team.”

A number of executives across the game see this WBC as a seminal moment for baseball – the time when everyone, even the holdouts, realized the grip Latin American players have on this game. There is deep concern that the U.S. simply isn’t producing players at the level it can and that the U.S. needs its own revolution to keep the talent pool deep. Perhaps this is unfounded – in 2012, 73 percent of major league players were from the U.S. … same as in 2007 – but the sense is pervasive enough that league officials are starting to study it.

Because there always will be Dominicans there happy to fill those spots, happy to spread the sport they feel is theirs. They’ve now got a trophy to back up that sentiment, to confirm what they believe: Nobody makes baseball players like the Dominican Republic, and that in another 50 years, the revolution will be complete and the game won’t look anything like it does today.